The story behind Mason's founding

The following piece is the first of a three-part series on the history of George Mason University. The information and research in this article is based off of “George Mason University: A History,” a project created by University Libraries’ Special Collections & Archives department.

The founding of George Mason University was the result of the efforts of many, but the story starts with one person: Charles Harrison Mann, Jr.

"Mann was a lawyer and a concerned citizen," said Robert Vay, digital collections archivist for University Libraries and one of the lead faculty on the George Mason history project. "He was mostly interested in education and mental health."

Mann was a practicing attorney in Arlington and Washington D.C. and would later be elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. An alumnus of the University of Virginia, Mann was serving as the president of the Northern Virginia Chapter of the University of Virginia Alumni Association when he received a phone call from then UVa President Colgate Darden, Jr. about the possibility of expanding higher education in Northern Virginia.

In 1949, Northern Virginia was constantly changing. Between 1940 and 1950 the population in Fairfax County alone had jumped from 41,000 to 98,500, a 140 percent increase. Additionally, many young families were beginning to settle down and start families after World War II and veterans were trying to attend college on the G.I. Bill. As a result, Mann and other UVa officials saw the need for a higher education institution in the region.

Although establishing a full-fledged university would take years of planning and construction, many felt that a good way to get a foot in the door was to create an “extension center,” which would work as a night school for working adults looking to take individual classes.

"It was all tied to the GI Bill and by soldiers coming home for school," Vay said. "[The facility] was going to be extension education…people trying to improve on the skills they already had."

Vay added that while UVa and Mann were working for an extension branch, they always had higher ambitions in mind.

"From the beginning they were planning for a four-year college," Vay said.

A local push for a UVa extension center

John Norville Gibson Finley, who worked in the Extension Division at UVa, was sent to Northern Virginia to begin the planning process. On Jan. 5, 1949, the first organizational meeting was held at Washington & Lee High School in Arlington.

An eight person exploratory committee comprised of local representatives and university officials officially sent a letter to President Darden on April 4, 1949 requesting that an extension center be created in the area. In the meantime, UVa’s Extension Division along with the local exploratory committee began the search for temporary space to house the administrative section and some classroom space for the extension center.

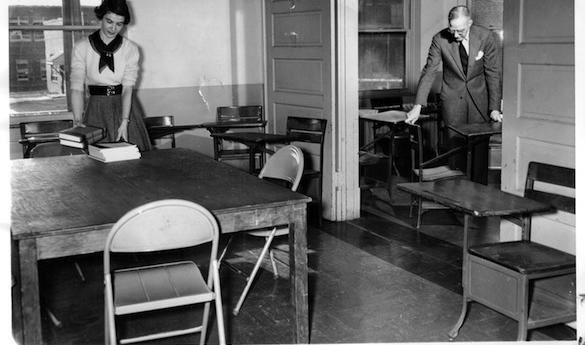

Washington & Lee High School, located in northwest Arlington, offered their space for the extension center. As one of the only high schools in the area, the location was already a focal point in the community where many local meetings were held. UVa’s Northern Virginia University Center was officially open on Oct. 1, 1949 with Finley as director.

Growing demand and the need for a larger institution

The following year was spent organizing, developing a curriculum and hiring faculty. Because young students were using the school during the day, all classes were offered in the evening. The center’s first semester offered non-credit courses such as conference leadership, public speaking, introductory electronics, literature of the Bible and rapid reading. For-credit courses included banking, accounting, math, engineering and architecture.

In the first semester, the center taught 20 classes and enrolled 478 students. The center offered 44 for-credit courses in the 1950-1951 academic year and had 665 students enrolled. By the end of 1952, 1,192 students had enrolled, a 79 percent increase in just two years.

"I think they were a little puzzled by the success," Vay said. "The [extension center] filled the need. It was conveniently located for people who wanted to continue their education."

Although both local citizens and university officials commended the center’s success, many felt that Northern Virginia still needed an institution for full-time students.

Another committee was created in January 1954 to advise the university on the existing extension center and to explore the possibility of expanding a branch of UVa. The committee would also decide whether or not to operate under UVa or to branch off and become an independent extension school.

However, in 1953, changes in the higher education policy allowed only one year of classes to be transferred towards a bachelor’s degree unless the institution was an officially established branch of a parent organization. As a result, the extension center would have to become a full-fledged branch of the university if credits were to be transferable.

"UVa would have to have its own physical branch," Vay said. "Its own faculty and its own facility."

Mann works towards a compromise

Later in 1955, the Virginia Advisory Legislative Committee, a joint group between the Virginia House of Delegates and the State Senate published a report entitled “The Crisis in Higher Education in Virginia and a Solution.” The report recommended that two-year branches of large, existing universities be created where there was a lack of higher education.

"This was the first thing the legislators saw on their desk at the beginning of the [legislative] session," Vay said. "They read it and they ate it up."

In the 1956 General Assembly session, C. Harrison Mann, Jr. who had been elected to the House of Delegates in 1954, proposed a bill that would officially establish a branch of the University of Virginia in Northern Virginia.

"Once Mann became a delegate he helped guide the branch process along," said Vay. "Mann said 'If we're going to get [a higher education facility], Northern Virginia is going to get it.' But he was trying to make deals with southern members of the General Assembly."

Some southern members of the General Assembly feared that creating an official branch would eventually lead a four-year institution in the area, and give UVa an upper-hand over existing institutions such as William & Mary and Virginia Tech. To help ease these fears, Mann added a clause to the resolution that ensured that it would only offer two years of classes to each student and that they would only construct instructional facilities and not dormitories.

With the passage of the bill, Northern Virginia could now build a permanent institution of higher education as a branch of the University of Virginia. Many questions still remained about where the branch would be located and prospects for independent university in Northern Virginia, which would compete with already well established universities in other parts of the state.

The next part of the series explains how George Mason College of the University of Virginia separated from its parent institution, and was officially established as George Mason University.